That’s the million-billion stats planet we live in.

And in that million-billion stats world, some strange things have been happening in the marketing arena.

An interesting piece of news came from an unexpected startup last month.

Buffer, a company considered one of the leaders in social media, announced that they had been failing on social media.

The introduction to their shocking announcement was brutally honest:

“We as a Buffer marketing team — working on a product that helps people succeed on social media — have yet to figure out how to get things working on Facebook (especially), Twitter, Pinterest, and more.”

Buffer has had the reputation of being completely transparent, from making their salaries public to showing consumers exactly where their money goes. Still, it was probably not an easy decision to share failure news in public.

Indeed, you could sense it in Kevan Lee’s hesitant words:

“… I’m a bit scared to publish: We’ve Been Failing on Social Media for the Past 2 Years,” he tweeted.

It didn’t take long before the article hit my newsfeed being shared by many marketing people I follow.

Was it time someone finally took the courage to say out loud the things we have been scared to confess?

So many people were joining the Buffer discussion.

While many were admitting their social traffic was also record low, some industry experts including Rand Fishkin were expressing opinions about why Buffer might have lost half of their social referral traffic.

Buffer wasn’t the first one to bring this up though. In parallel, some other influencers seemed to have been sharing similar thoughts over the last year.

Is this the social media fatigue everyone has been talking about?

Have we reached a moment where we can no longer stand the idea of ‘liking’ yet another marathon or baby picture of our friends?

Maybe we’ve developed a magical eye skill to scan tweets without engaging with them. The truth is:

Social reach is just one side of the story

We are starting to see content saturation in many forms. The concept of information overload isn’t new, it’s just getting intense. Steve Rubel called it “attention crash” eight years ago.

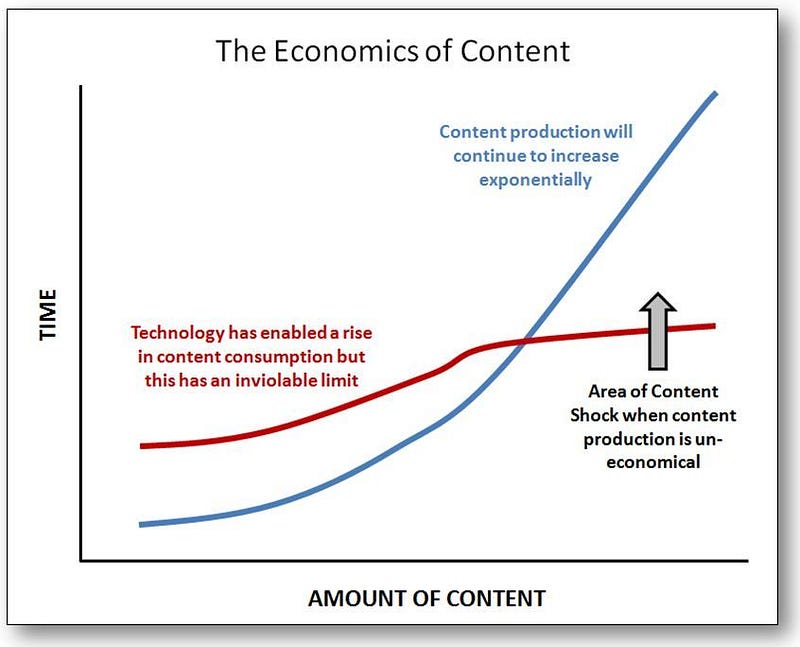

And in his popular “Content Shock” post last year, best-selling author Mark Schaefer told us content marketing might not be a sustainable strategy.

He suggested we were about to reach a point where content production would intersect our human capacity to consume it. And it would become uneconomical to produce content afterwards.

While some argued that there would be no content shock, a strong part of Schaefer’s thesis relied on the assumption that each human has a physiological, inviolable limit to the amount of content they can consume.

And that limit would create a ceiling beyond which our messages would receive little or no attention from the audience.

Indeed, a very recent study conducted by Moz and Buzzsumo analysed 1 million articles and found that the great majority of content got little material response: 50% of the content received 2 or fewer Facebook interactions (shares, likes, or comments) and 75% showed no external links.

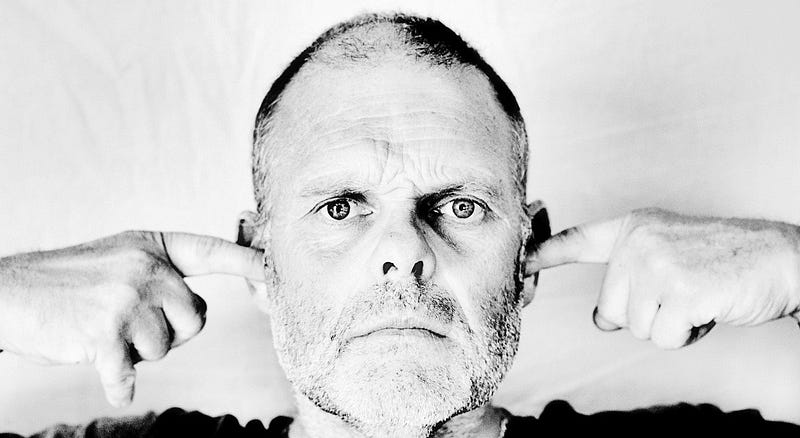

Is this the beginning of a new era we might soon call “#ConsumerTakeOver”?

An era where consumers finally take control and react by ignoring our messages.

An era where they start muting the noise, blocking ads, and cleaning up their cluttered newsfeed by un-liking pages, ignoring tweets, or unsubscribing from newsletters.

The truth is most of us got it wrong. We religiously followed the advice of experts to publish content consistently and flooded the world with ‘me-too’ blog posts.

“The thing is, a lot of these experts cut their teeth in the early years of the Web, when 500-word blog posts could win you fame and fortune,” saysMarketingProf’s Puranjay.

We scheduled 12 tweets per day just because they told us it was OK to tweet every two hours. We confused self-promotion with self-expression and found aggressive ways to increase the number of our followers and page views.

And along the way, we forgot about her, the consumer. We forgot she was the reason we started our businesses in the first place.

The Engagement Magic

And the trouble with focusing on growth before you have retention

David Ogilvy, the father of advertising as the world called him, warned us 52 years ago not to underestimate the power of consumers:

“The consumer isn’t a moron. She is your wife.”

In today’s modern world of gender equality, he would probably rephrase it to “he/she is your spouse.” But his inspiring words make it pretty clear that we shouldn’t take any consumer for granted or insult their intelligence.

The rules of the game in the online space are changing like never before.

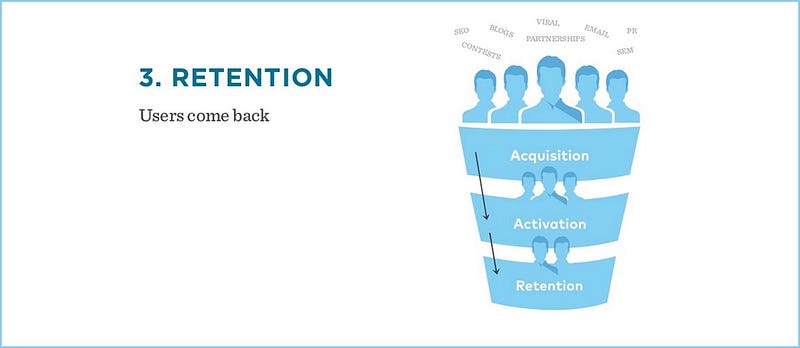

In a world where consumers become increasingly selective over what they consume, retention is emerging as a key factor that differentiates the successful from those who fail.

Retention is the most important factor in traction and growth according to many, including Brian Balfour, VP Growth at Hubspot. Tarun Mitrahighlights its importance by noting:

“If you invest in growth before you have retention, you’re renting users, not acquiring them.”

We might have thousands of users, followers, or customers. But how many of them are true fans?

How many of them read every single article we publish or click on every single tweet we send? How many of them actually pay attention to our company newsletters?

Instead of trying to attract more eyeballs in an unquenchable thirst for never-ending growth, we need to pause and learn to engage the audience we already have.

Tribe

COMMUNITY

True Fans

While most of us were busy flooding people’s newsfeeds with posts and tweets, few others got it right from the very beginning.

They were smart enough to realise that even just five engaged true fans were more valuable than five thousands followers.

I’m talking about those who knew that the secret to success was to find a way to do more for others than anyone else is doing. They are the ones who have been building a community of true fans by engaging them through extreme value creation.

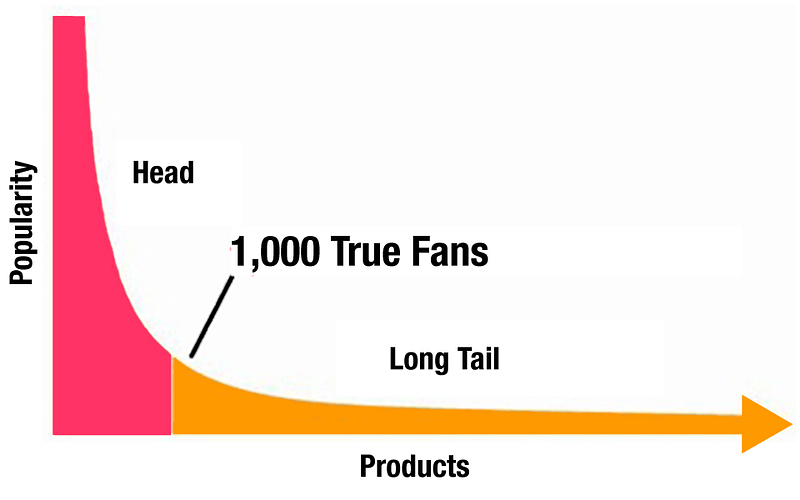

Kevin Kelly’s principle of 1,000 True Fans suggests that a creator (such as an artist, musician, photographer…) needs to acquire only 1,000 True Fans to make a living. In his words, a true fan is:

“someone who will purchase anything and everything you produce. They will drive 200 miles to see you sing… They have a Google Alert set for your name… They come to your openings… They can’t wait till you issue your next work. They are true fans.”

But let’s make three things crystal clear about audience engagement:

1. Engaged ≠ True fan

Kelly’s true fans principle relies on the assumption that each true fan spends $100 per year to help the creator make a living. This economical contribution is what differentiates true fans from others.

This is also where we get confused the most. We think that if we keep giving and creating value for people, they will all give back and buy whatever we are selling when we ask them in the future.

Though businesses exist to make a profit, we need to understand the subtle difference between an engaged person and a true fan. Just because someone engaged with or showed interest in, say, your tweet, product, or newsletter doesn’t mean she or he will purchase anything you produce.

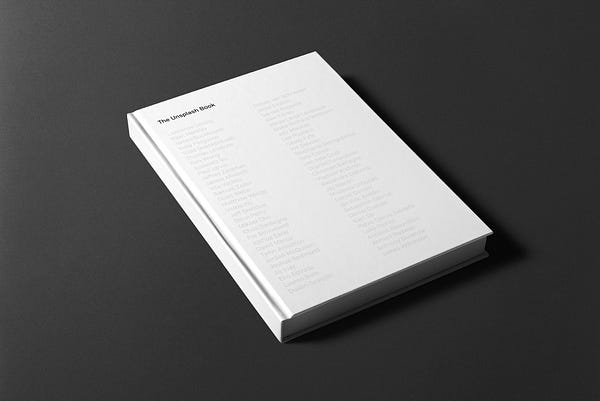

One of the harsh lessons I learnt came from a recent Crew project I joined last week. Being overly confident with my previous freelancing experience, I was pretty sure we could convert most of the Unsplash newsletter subscribers into backers of the Unsplash book campaign we launched on Kickstarter.

After all, the guys at Crew had never asked for anything in return other than just giving away free photos since 2013. And the site had the most engagement per photo of any photography site in the world.

So we sent out what we believed was a great email campaign to over 200K people with all the details.

The results? Ehm…

Well, we had trouble even reaching 3k people out of those 200K subscribers. And you can make an educated guess about how many of those 3K actually backed the project (hint: similar conversion rate applies).

While this conversion is only a fraction of what it could have been a few years ago, that’s the million-billion stats world we live in. A world where a little bit of value is no longer good enough to hold someone’s attention long enough to potentially turn her into a true fan.

It’s very easy to forget about value creation by feeling the pressure of short-term gains, but there is more when it comes to an audience:

2. The power of an invisible audience

Your tweet or article didn’t get the attention you think it deserved? Not enough retweets or shares? Well, here is some good news. Your audience might be way bigger than you think.

A joint study by Stanford and Facebook found that your actual audience size is four times larger per post than you think. Your invisible audience, or the ‘quiet observers’, might also have some friends who might be your future fans.

Amanda Palmer highlights the fact that the relationship building between the creator and fan is not just in one direction, but in many. Mike Masnick calls it “the artist giving to fans, the fans giving to artists and, beyond that, the fans giving to other fans and artists giving to other artists.”

3. There is no right way to engage an audience

There is so much to learn from those who have built a community of true fans by engaging their audiences. Here are a few ways to do it:

- Find a unique voice: Paul Jarvis calls his true fans his “rat people” and is famous for using a sharp sense of sarcasm to engage his tribe.

- Take accessibility to the next level and be available: Justin Jackson, a guy crazy about making stuff, has built a community of makers on a Slack channel called “Product People Club.” While some influencers make themselves available even on a 1-on-1 Slack chat, others engage their tribes by being responsive on Twitter or offering AMAs, products, live chats, feedback sessions…

- Make few people feel special: “Make your first 100 users feel like thought leaders,” recommends Erik Torenberg, explaining how they leveraged community to grow Product Hunt. Giving exclusive access to only a few people or sending gifts are some possible ways.

- Help customers get better at what they do: According to Helpscout’s Gregory Ciotti, “Nobody wants to be a camera expert — they want to be a great photographer. Success means helping customers become better at what they do.” Startups like Helpscout or Buffer delight their audiences by publishing top-notch content that improves the businesses of their customers.

- Identify a niche and build a community around it: Instead of employing traditional marketing tactics, Hubspot’s co-founder Dharmesh Shah coined a brand new term nine years ago: ‘inbound marketing’. This not only boosted the awareness of Hubspot but also gave birth to one of today’s most popular community websites inbound.org. The same happened when Sean Ellis built a community of people passionate about growth on growthhackers.com, after he coined ‘growth hacking’.

- Use side project marketing to create extreme value: In a world where blogging takes ages and ads no longer work, I tried to explain in my latest post how side project marketing can be an alternative growth machine. levels.io is yet another serial maker who has built a community of digital nomads by launching tools, from Nomad List to Nomad Trips.

How many of your followers are your true fans? What are you doing to engage them?

It’s always nice to talk about fancy metrics or growth hacking terms like A/B tests and DAUs. But when it comes to growth, how many of us set a qualitative target such as “Delighting your tribe”?

Content shock may or may not arrive, but this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t fix what we already know hasn’t been working.

Your customer isn’t a moron. She is your wife.

And it looks like it’s finally her turn to teach us how to do this engagement thing right.

By Ali Mese

Bringing you independent, solution-oriented and well-researched stories takes us hundreds of hours each month, and years of skill-training that went behind. If our stories have inspired you or helped you in some way, please consider becoming our Supporter.